The Treaty Battleships By Chuck Hawks In this essay I propose to examine the Battleships produced by the major world sea powers after the signing of the landmark 1922 Washington Naval Treaty. The 1922 Treaty was replaced by the subsequent London Naval Treaties of 1930 and 1936. German naval rearmament after World War I was constrained by the Treaty of Versailles, which initially limited German battleships to 10,000 tons and 11 inch main battery guns. In 1935, the Anglo-German Naval Treaty allowed Germany to build up to 35% of the surface ship strength of the Royal Navy and limited the maximum size of German battleships to 35,000 tons, the same size limit the other major powers had agreed to in the Washington and London treaties (to which Germany was not a signatory). The Washington and London treaties had a major impact on the capital ships of all nations. THE NAVAL TREATIES The Washington Naval Arms Limitation Treaty of 1922 was the result of political pressures to prevent a massive naval arms race between the victorious nations, as they jockeyed for dominance after the end of the First World War. The pre-war Anglo-German naval arms race was seen as one of the factors contributing to the outbreak of the Great War and the citizens of a war weary world did not want a repeat. Moreover, Britain, France and Italy had been financially drained to various degrees by the War, while Japan and the U.S. were relatively unharmed economically. However, the Japanese industrial base was no match for that of the United States (which by 1920 was the only nation in the world capable of winning a renewed naval arms race), while the U.S. lacked the political resolve to engage in an expensive arms race. These factors combined to bring Britain, the U.S., Japan, France and Italy to the bargaining table to hammer out the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. The result, which made all of the Admiralties involved unhappy, was the scrapping of many older capital ships, the cessation of new construction (with a few very limited exceptions) and the adoption of the 5-5-3-1.7-1.7 capital ship tonnage ratios (Britain and the U.S. equal at 5, Japan at 3, France and Italy at 1.7). These ratios approximately reflected the balance of power at the time. Total future fleet tonnage was fixed. The size of cruiser fleets was not regulated, so it became important to ensure that cruisers did not simply become battleships in all but name. Cruisers were therefore limited to 10,000 tons and 8 inch guns (6 inch guns might have been more appropriate, but the British had just commissioned the Hawkins class cruisers with 7.5 inch guns and insisted on retaining them). It was agreed that existing capital ships would not be replaced by new construction until they were at least 20 years old. There was to be a battleship building "holiday" until the end of 1931. The modernization of existing capital ships was allowed, but regulated. There were other provisions and trade-offs that do not concern us here. The provisions that directly affected future capital ship construction included a limit on main battery gun caliber of 16 inches and a limit on displacement of 35,000 tons "standard." Standard displacement was defined as ready for sea, but without reserve feed water and fuel. The Americans wanted to also exclude stores, but this was not accepted. The purpose of the standard displacement figure was to reduce the disparity between long and short range battleships. The interpretation of standard displacement by the various signatory nations proved to be much more flexible than intended or foreseen. The success of the Washington Treaty and the world depression that was signified by the U.S. stock market crash in 1929, brought further attempts at limitation. The result was the London Naval treaty of 1930. Cruiser and destroyer construction was now limited and the numbers of capital ships further reduced. The numbers (not tonnage, this time) of capital ships was set at 15-15-9 (U.K., U.S., Japan). Several useful capital ships were scrapped or demilitarized as a result of this treaty, among them the excellent British battlecruiser Tiger. The capital ship building holiday was extended until the end of 1936 (again, certain exceptions were made). A significant, though unintended, result of these treaties was that in all of the world's navies, capital ships became so scarce that in the Second World War they were seldom employed offensively, for fear of loss. Heavy cruisers, by default, took over many battleship roles. Only the United States built enough third generation battleships to use them aggressively, by then mostly in secondary roles. (The aircraft carrier had become the primary arbiter of sea power in the Pacific war.) Late in the war, after her carrier air power had been neutralized, Japan sacrificed her remaining battleships in desperate and futile offensive operations. By 1934, however, change was in the wind. Japan notified the other powers that she was withdrawing from the Naval Treaties, no longer willing to accept humiliating (as she perceived it) treaty enforced inferiority. Negotiations in 1935-36 resulted in abandonment of the ratios, although the existing limits on battleship size and guns were maintained. The new London Treaty was signed on 25 March 1936. The British lobbied hard for, and got, a further reduction in gun caliber to 14 inches, but an escape clause allowed 16 inch guns if a non-signatory refused to guarantee adherence to the 14 inch limit. Japan's intentions in this regard were unknown, but amid persistent rumors of Japanese super battleships designed to mount 16 inch or 18 inch guns, the U.S. invoked the escape clause in July 1937. This happened too late for the British to revise the design of the King George V class, but in time for the Americans to increase the battery (but not the armor) of the North Carolina class. Another escalator clause included in the 1936 treaty allowed signatories to increase tonnage to 45,000 if a non-signatory did not adhere to the treaty limit. Japan completely ignored the 35,000 ton limit and Germany and Italy adhered only nominally, building 40,000+ ton battleships they claimed were only 35,000 tons standard displacement. Only the U.S., Britain and France actually signed this last treaty, or made any attempt to adhere to the 35,000 ton displacement limit. By signing the 1936 London Treaty, the Allies were limiting themselves while their potential enemies did as they pleased. An analogous situation is seen today in efforts to control everything from nuclear weapons to land mines. The only nations that actually abide by such restrictions are the ones who pose no terrorist threat to world peace in the first place. With the start of the Second World War, all Treaty obligations became null and void. The U.S. Iowa class, the British Vanguard and the French Jean Bart were the result when these powers were finally able to build the battleships they wanted. These ships are beyond the scope of this essay, but are covered in The Post-Treaty Battleships. Still, it is worth noting that even these ships were heavily influenced by previous treaty considerations. The first ships built under the treaty restrictions were the British Nelson class, laid down in December of 1922. A long treaty enforced pause in battleship construction then ensued until the laying down of the first of the Italian Littorio class in 1934. (The German Deutschland and French Dunkerque classes were built in the intervening years, but they are covered in my essay Battlecruisers, Large Cruisers and Pocket Battleships of World War II.) The German Scharnhorst class battleships were laid down in 1935, accompanied by the French Richelieu, also in 1935. These were followed by the last of the treaty battleships to be laid down, the British King George V class in 1937, the American North Carolina class in 1937-38 and South Dakota class in 1939-40. These are the ships that will be covered in this essay. The basic specifications quoted for all ships are taken from Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922-1946. Doing this has the advantage of uniformity, plus I regard Conway's as exceptionally authoritative, based as it is on a major reevaluation of published information with the advantage of hindsight and previously unpublished information from sources only recently available. NELSON class  The British Nelson and Rodney were the first battleships laid down under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. In the years immediately prior to the adoption of the treaty, the U.S. and Japan had each completed a two ship class of battleships mounting 16 inch main battery guns. These four ships, Colorado and Maryland, plus Nagato and Mutsu, each carried 8-16 inch guns on a normal displacement of 32,600t (U.S.) to 33,800t (Jap.). They were the most powerful battleships in the world at the time of the signing of the treaty. The British demanded, and received, the right to immediately build two 16 inch gun battleships of their own as equalizers under the terms of the new Washington Treaty. The Nelson class thus became the last of the second generation battleships and the first of the treaty battleships. Prior to the signing of the treaty, the British had been working on the design of new classes of large battlecruisers and battleships. The former being fast ships mounting 16 inch guns and the latter slower ships mounting 18 inch guns, both on displacements of 46,500-48,000 tons. After agreeing to the 35,000 ton standard displacement limit, British designers were faced with the necessity of attempting to combine the most valuable features of these ships into the smaller hulls of the new treaty battleships. The attempt to do so produced the strangest looking battleships ever launched by the Royal Navy. All three triple 16 inch gun turrets were mounted forward of a tower superstructure, on a flush deck hull. The single funnel was about 3/4 of the way aft and the 12-6 inch secondary guns (arranged in three twin turrets per side) were further aft yet, as was the mainmast. Over half of the entire hull length was taken up by the very long bow section, where the three big gun turrets were arranged with the middle (second) turret super-firing over the first and third turrets. Naturally, they suffered from a huge blind arc aft. The benefit of this arrangement was supposed to have been a shorter armored belt (which was internal and inclined at 15 degrees) and a more compact layout. In service it became evident that the Nelson's layout had been a mistake and it was not repeated. Another compromise showed in the adoption of twin screws, also to save weight. Despite their small 670 yard tactical diameter, their very long fo'c's'le and twin screws made them clumsy ships to maneuver. Although in the event it did not matter, the adoption of twin screws also made them especially vulnerable to underwater damage aft. Another unfortunate compromise was their slow design speed of 23 knots. This rendered these powerful and relatively modern battleships unsuitable for many first line tasks in World War II. Interestingly, American designers considered a similar all-main-turrets-forward design for what became the North Carolina class, also seeking to conserve precious treaty tonnage, but abandoned it when it became evident that a conventional 3x3 layout with two turrets forward and one aft was actually more economical. There were other problems with this class. Their 16 inch main battery turrets gave considerable trouble and were far less satisfactory than the previous excellent 15 inch / 42 caliber twin mounts. The defects were eventually corrected and Rodney performed well against Bismarck in May of 1941. The 16 inch guns had a maximum elevation of 40 degrees and fired a 2,048lb (later 2,375lb) projectile at a muzzle velocity of 2,614fps to a range of 39,800 yards. Broadside weight was 18,432 (later 21,375) pounds. The 6 inch secondary and 4.7 inch QF power operated mounts also gave trouble and unfortunately their rate of fire fell considerably below expectations. They were also armed with two 24.5in underwater torpedo tubes, always a mistake in battleships. During WW II, Nelson took an Italian 18 inch torpedo near her torpedo room and the ship was flooded with 3,750 tons of water. Not surprisingly, when she was repaired, the torpedo installation was removed. Rodney claimed one torpedo hit on Bismarck late in that action and, if true, it is the only time in history that one battleship succeeded in torpedoing another. All in all, Nelson and Rodney do not sound like very satisfactory battleships and in many respects they were not. They even came out well under the allowed tonnage, at 33,313 tons standard displacement. However, it should be remembered that they were the most heavily armored and armed battleships of their time, superior to most of their contemporaries. Their specifications were as follows:

Both ships were laid down on 28 December 1922. Nelson was completed in August 1927 and Rodney in November 1927. The principle change during their lifetime was the wartime increase in light AA guns and the addition of radar. For example, Nelson had six octuple 2pdr pompom, four quadruple 40mm Bofors and 60 to 70 20mm Oerlikon light AA guns by the end of the war. As with all wartime battleships, displacement crept upward as new equipment was fitted, increasing by two to three thousand tons by 1945. Both survived WW II and were broken up in 1948. Both had active war careers. Nelson was mined twice and torpedoed once. The highlight of Rodney's career was undoubtedly when she successfully fought Bismarck. This famous action, in which battleships King George V (Admiral Tovey's flagship) and Rodney finally confronted the long suffering and damaged Bismarck, has been recounted many times. There is no need to go into it again here, except to point out that while Bismarck had been torpedoed in the stern and her rudders jammed, her fighting potential was undiminished. In the final engagement KG V, being the flagship, is most often mentioned. However, my research leads me to believe that it was actually Rodney that was primarily responsible for the defeat of Bismarck. The 1922 treaty battleship quickly overwhelmed the 41,700 ton pride of the Kreigsmarine with her accurate 16 inch gunfire, pounding her into flaming junk (with some help from KG V). Bismarck never hit Rodney at all. By the end of the battle, Rodney had closed the range to the point she was able to fire two torpedoes at Bismarck, as mentioned above. One appeared to hit, but had no appreciable effect on Bismarck. There is no way a slow (22 knots at the time she engaged Bismarck) second generation battleship like Rodney should have been able to catch, let alone out shoot, a new third generation battleship approximately 1/3 larger than herself. Yet it happened and Rodney proved that once she got an adversary within range of her guns, her odd design was quite satisfactory. LITTORIO class  Umberto Pugliese was the Italian director of design in 1930 when work started on the four ships of the Littorio class. They were to be the first large battleships laid down since the Nelson class of 1922 and the first Italian capital ships since WW I. Littorio and Vittorio Veneto were laid down on 28 October 1934. The third ship, Impero, was laid down on 14 May 1938 and the final ship, Roma, on 18 September 1938. In keeping with Italian tradition, they featured many innovations. Perhaps the most notable were their unusual "Pugliese" underwater protection system and their high velocity guns. They were also the first full size fast battleships, being intended as a response to the 29.5 knot French Dunkerque class battlecruisers laid down in 1932. Although nominally 35,000 tons, by the time the design was complete and the first pair was laid down in 1934, the true displacement had grown to over 40,000 tons. The Fascist government of Benito Mussolini clearly had no more respect for its treaty commitments than other totalitarian dictatorships, before or since. These ships were designed to carry nine 15 inch guns (3x3), even though the London Treaty allowed 16 inch guns. The choice of caliber was determined by the limitations of Italian ordinance manufacturing capabilities. Instead, they built an innovative, high velocity 50 caliber gun which fired a 885kg (1,947 pound) AP shell at 2,800fps, generating very high energy. The maximum range was 46,800 yards at 35 degrees elevation. Unfortunately, the barrel life was unusually short. Broadside weight amounted to 17,523 pounds. Magazine stowage was only 74 rounds per gun. The layout of these ships was conventional, with two triple turrets forward and one aft. The aft triple turret was in the "X" position, raised on its barbette to the same height as the forward super-firing "B" turret, which was unusual. I have never heard the official explanation for this. Could it have had to do with increasing space below the aft magazine for anti-torpedo protection? Ordinarily, designers try to keep the great weight of main battery turrets and barbettes as low as practical, both to improve stability and save the weight required by the very heavy armor on barbettes. A tower superstructure and twin stacks gave the ships a powerful appearance. The quarterdeck was cut away and a catapult for seaplanes installed there. The unconventional Pugliese underwater protection system consisted of a 40mm torpedo bulkhead that curved up from the outer bottom and then extended outboard to meet the lower edge of the armor belt. Within the space thus created between the void double bottom and this torpedo bulkhead was a liquid filled compartment. Within that was a void longitudinal drum with a diameter of 380cm with 6mm walls. The idea was that the explosion of a torpedo warhead would collapse the void drum within the liquid filled compartment, thus absorbing most of the explosive energy. The torpedo bulkhead was supposed to catch splinters and prevent further damage. This system was also adopted by the Russians for their Sovyetskiy Soyuz class super battleships. (See The Battleships That Never Were for a description of these ships.) Unfortunately, like most anti-torpedo systems, it did not work as well in practice as it did in theory. These were fast ships, but not as fast as they were sometimes credited with being. They did not sacrifice armor for speed, they simply exceeded the treaty limit on displacement by a wide margin, so that they could have both. On trials, Littorio made 31.3 knots at 41,122t. Their sustained sea speed was closer to 28 knots. They were designed with bulbous bows, but were troubled by vibration and the bow was consequently modified and lengthened by six feet. The second pair were further lengthened and the sheer at the bow increased. Littorio's specifications follow:

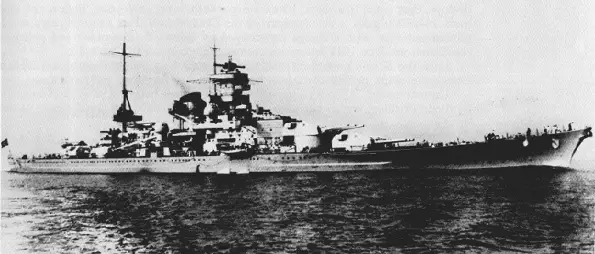

Littorio was completed on 6 May 1940, Vittorio Veneto on 28 April 1940 and Roma on 14 June 1942. Impero was never completed. Roma was sunk by two German radio controlled glider bombs while steaming to Malta to surrender. The first struck amidships and passed clear through the ship, exploding under the hull. The second caused an explosion of the forward magazines, breaking the ship in two. The other two ships survived the war, were turned over to the U.S. (Littorio) and U.K. (Vittorio Veneto) as war reparations in 1947 and scrapped in the early 1950's. Impero was captured incomplete by the Germans after the Italian surrender and used as a target. She was sunk by Allied aircraft in 1945 and scrapped at Venice in 1947. War modifications included the fitting of additional AA guns. All three received radar during 1942-43. Endurance was about 4,700nm at 14 knots. These battleships had the somewhat checkered war careers typical of Italian heavy ships. Littorio was hit by three torpedoes at Taranto in November 1940. She took light damage in the Battle of Sirte in March 1942, was damaged by air attack in June 1942 and April 1943. She was renamed Italia shortly after the fall of Mussolini in July 1943. On her way to Malta to surrender in September 1943 she was hit by a German radio controlled glider bomb and her hull was seriously damaged. Vittorio Veneto was torpedoed by a British aircraft in the Battle of Matapan in March 1941. She was torpedoed again by the British submarine Urge in October 1941, and received minor bomb damage at La Spezia in June 1943. Roma was also damaged by air raids at La Spezia in June 1943, before being sunk in September 1943 on her way to Malta, as described above. None of them contributed much to the Italian war effort. Had one of them fought it out with the French Battleship Richelieu (more about her later) for dominance in the Mediterranean, it would have been interesting. However, the war was not kind to the Italian or French navies. SCHARNHORST class  These two interesting ships, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, were laid down on 16 May 1935 and 3 May 1935, respectively, a few months before the signing of the Anglo-German Naval Treaty that justified them. They grew out of a design for a super-Deutschland commerce raider, displacing about 19,000 tons and more heavily armored than the previous class, but retaining the six 11 inch gun main armament (two triple turrets) of their predecessors. Another design incorporating eight 12 inch guns (4x2) and lighter armor was also considered. The German Admiralty argued that given the increased size, a third triple 11 inch turret should be carried and in the end this view was accepted, even though it would raise the displacement to 26,000 tons. After the Anglo-German treaty was signed, the revised German Navy program officially included two small battleships of 26,000 tons, armed with nine 11 inch guns. Ultimately, as completed, S and G evolved into full size fast battleships of nearly 35,000 tons. Since the Anglo-German Naval Treaty allowed guns up to 16 inch caliber, Hitler ordered the two new ships armed with 15 inch guns. These would be based on the German First World War 15 inch twin mount. Unfortunately, the development of the new 15 inch guns would delay the completion of the ships, so it was decided to initially arm them with the existing 11 inch triple turret and then rearm them with the new twin 15 inch mounts as soon as feasible. Both turrets were designed for the same size barbette and the shell handling rooms, etc., were designed to accommodate the larger 15 inch shells. World War II intervened and the ships were never rearmed. Following severe wartime bomb damage to the forward part of the ship in November 1942, Gneisenau was to be rebuilt with the six 15 inch gun armament (3x2) planned earlier. However, project was canceled in 1943, as time began to run out for the Third Reich. The Scharnhorst class were handsome ships, which is a tribute to German design, especially considering the unusual British Nelson and French Dunkerque classes, with their entire main batteries concentrated forward, which preceded them. S and G were conventional in layout, with two triple turrets forward and one aft. Their single large funnel was located amidships with the hanger, catapult and cranes for their floatplanes behind it and their secondary guns were arranged conventionally along each side of the superstructure. In 1939, a clipper bow, called the "Atlantic" bow, was fitted to both ships, which had proved to be wet forward in heavy seas. Gneisenau could be distinguished from Scharnhorst by the position of their mainmasts. Gneisenau's mainmast was stepped immediately abaft her funnel, while Scharnhorst's was stepped further aft, between her catapult and her aft main battery rangefinder. The Scharnhorst mast position was more attractive. The 12-5.9 inch secondary guns were mounted in four twin and four single turrets. It had been planned to use all twin mounts, but there were single mounts intended for the canceled fourth and fifth Deutschlands available and they were pressed into service. The 5.9 inch gun was a single purpose weapon, so S and G also had 14-4.1 inch dual purpose guns in twin mounts. A better arrangement might have been to standardize the secondary battery, replacing all of the 5.9 inch mounts with 4.1 inch twin mounts. The resulting 30-4.1 inch (15x2) secondary battery would have given these ships an outstanding heavy AA capability, while still providing adequate protection against torpedo boats. The new German 11 inch gun fired a 700 pound AP shell to a claimed maximum range of 26 miles. The firing rate was 2.5 rounds per minute. Maximum elevation was 60 degrees. Broadside weight was 6,300 pounds. These figures far exceed those of the WW I German 11 inch gun, which fired a 670 pound shell to a maximum range of about 30,000 yards (17 miles). The latter figures are quoted in Jane's Fighting Ships as also applicable to the WW II German 11 inch gun, but I now believe them to be in error. J. N Westwood, in his book Fighting Ships of World War II, is quite specific about the differences between the WW I and WW II German 11 inch guns. The Scharnhorsts carried on the German First War tradition of adequate armor protection and detailed internal subdivision. Another plus was their provision for sufficient directors for their AA armament and their excellent, fully stabilized, tachymetric AA fire control system. A minus was their high pressure machinery, which proved unreliable in service (a familiar refrain regarding German ships of this general vintage). Geared steam turbines were used, because diesel engines of sufficient displacement and power were not available. Even so, their range of 8,400nm at 17 knots was considerable. The design speed was 32 knots, although there is some question as to whether either actually achieved this speed on trials. German capital ship designers were enamored of three propeller shaft (rather than the more conventional four shaft) design and the Scharnhorsts were so equipped, as were the following Bismarck class. This layout worked to Bismarck's disadvantage when she was torpedoed in the stern. Scharnhorst class specifications follow:

Scharnhorst was commissioned on 7 Jan 1939; Gneisenau on 21 May 1938. During the winter of 1938-39, both were equipped with the "Atlantic" bow, which increased their overall length to 770 feet 8 inches. The second catapult, on top of the aft 11 inch turret, was removed from both ships at about the same time and Scharnhorst was equipped with a tripod mainmast. As with other WW II capital ships, AA armament was increased as a result of wartime experience. Scharnhorst received 24 additional 20mm light AA guns and Gneisenau 12 more. Scharnhorst was fitted with six 21 inch torpedo tubes (3x3) removed from the light cruiser Nurnberg. During the first half of the war, the two ships spent most of their time together and they had quite successful war records. Scharnhorst became the most active and successful of the German battleships. In November 1939 they sailed into the North Sea, attempting to break out into the Atlantic. Instead, they encountered the British Armed Merchant Cruiser Rawalpindi, on distant blockade patrol, which they sank. On 9 April 1940, while covering the German invasion of Norway, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau exchanged gunfire with the British battlecruiser Renown. Scharnhorst was hit by Renown's 15 inch guns and the pair withdrew at high speed, rather than fight it out with the old British battlecruiser. Later in the same operation they sank a tanker and an empty troopship, then fell upon the British aircraft carrier Glorious and escorting destroyers Ardent and Acasta. The German battleships sank all three British warships, although one of the destroyers put a torpedo into Scharnhorst, flooding her with 2,500 tons of water. This likely saved a nearby convoy, as the Germans were forced to retire to have the torpedo damage repaired. After repairs, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau broke out into the Atlantic and sank 22 ships between 22 Jan and 23 Mar 1941, when they put in at Brest on the occupied Atlantic coast of France. Both ships were frequently bombed by the RAF while at Brest and after the loss of the Bismarck, which had hoped to join them there, plans were made to bring them home to Germany. 11-13 February 1942, the famous "Channel Dash." S and G, along with heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen (survivor of the Bismarck debacle), ran from Brest, through the Straits of Dover, to safety in Kiel. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau both hit mines off the coast of Holland during the passage. Both went into dry-dock at Kiel for repair, where a few days later Gneisenau was hit by British bombers and her whole forecastle was blown off. It was at this time that the plan to go ahead and convert her to 15 inch guns was put into effect, but this conversion was never completed. Late in the war the hulk was sunk as a block ship in Gdynia harbor. Scharnhorst was repaired by October 1942 and in March 1943 she was sent to Norway. From there she, in company with battleship Tirpitz, bombarded the Norwegian weather station on Spitsbergen Island. I have been to Spitsbergen Island, which is very far north in the Arctic Ocean, and it is hard to imagine anything of sufficient military value there to warrant the attention of two battleships. Just surviving against the elements is difficult enough in that cold and lonely place, which is frozen within the Arctic ice pack during the winter. Scharnhorst's last operation was against a convoy en route to Murmansk, Russia. On 26 December 1943, Scharnhorst fought the Battle of North Cape. This famous incident, the last battleship duel of the European war, was precipitated when the Scharnhorst and five destroyers attempted to interdict convoy JW 55B in vile weather off the North Cape of Norway. The situation on the Eastern front had worsened to the point that the German High Command was willing to give the naval force commander on the scene, Rear-Admiral Erich Bey, tactical freedom for the first and only time in the entire war. It is striking that the weather conditions were very similar to the New Year's Eve Battle of the previous year, only worse. (As an aside, I might mention that when I visited the North Cape in the middle of July, it was cold with a light rain and a heavy fog that cut visibility to a few yards. There is a small plaque there commemorating Scharnhorst's last battle). In the New Year's Eve Battle, the heavy cruiser Hipper, pocket battlecruiser Lutzow and six destroyers, failed to destroy a convoy bound for Murmansk. They were driven off, in conditions of near zero visibility, by the British escort under the command of Robert Burnett, consisting of light cruisers Jamaica and Sheffield with five destroyers. British superiority in radar and tactics had more than compensated for the German ships' superiority in heavy guns. Now, a year later, the disparity between British and German radar had only worsened. Scharnhorst and her five destroyers put to sea from Alten Fjord on Christmas Day. The next morning (the 26th), Admiral Bey deployed his destroyers in a scout line on a south-westerly course, while Scharnhorst continued on to the north. The German force was divided. You would think that after four years of war German Admirals would have learned not to divide their numerically inferior forces, but apparently not. As Scharnhorst blundered around in the fog and snow, plunging into heavy seas, she was suddenly engaged by the British heavy cruiser Norfolk and the light cruiser Belfast. The light cruiser Sheffield trailed the other two, but could not get within gun range. This cruiser force was again commanded by Vice-Admiral Robert Burnett, hero of the battle against Hipper and Lutzow the year before. Almost immediately an eight inch shell knocked out Scharnhorst's forward radar. She was left almost blind in the prevailing conditions of very poor visibility. She maneuvered to escape the British cruisers, succeeded, then turned back to her northerly course to again seek the elusive convoy. Admiral Bey tried to summon his destroyers, but by then they were far away and unable to make good speed, because of the heavy seas. Bey then ordered them farther to the west to search for the convoy. Aerial reconnaissance advised Bey of an enemy naval force to the southwest of him (between his position and safety), but he continued north. Shortly after noon, Scharnhorst was again surprised by the British cruisers. A twenty minute gun battle ensued, in which Scharnhorst scored heavily on Norfolk. Sheffield dropped out with engine trouble and the other two British cruisers fell back and began shadowing the German battleship. Bey made no attempt to shake off the British cruisers, instead ordering his destroyers to meet him back at Alten Fjord, and set course for home. Admiral Bey's false sense of complacency was shattered four hours later when starshell illuminated Scharnhorst and radar directed 14 inch shells from the battleship Duke of York, plus six inch shells from the light cruiser Jamaica, started falling around her. Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser's covering force had arrived. From approximately six miles away Duke of York straddled the German battleship. Scharnhorst returned fire and ran to the east to open the range. After twenty minutes of this running gun battle, Scharnhorst had been hit repeatedly. Her forward turret was jammed and a hit aft caused flooding that slowed her slightly. Nevertheless, she had opened the range to 10 miles and both battleships temporarily ceased firing. A few minutes later two destroyers crept up on each side of the German battleship. Scharnhorst's lookouts spotted the pair of destroyers to port and she engaged them with her secondary battery. However, the starboard pair got to within one mile before being spotted and put a torpedo into her. As she turned to avoid them, the port side pair pumped three more torpedoes into her. One torpedo hit flooded a boiler room and Scharnhorst's speed dropped to eight knots. Quick work in the engineering spaces got her speed back up to over 20 knots, but it was not enough. Duke of York closed the range and opened fire, joined by all three cruisers and four more destroyers. 14 inch shells and multiple torpedo hits from the cruisers and destroyers sank the Scharnhorst after 36 minutes. Only 36 of her crew survived the battle and the icy water. This battle is often referred to as the last single ship battleship duel, but it wasn't, really. Scharnhorst was overwhelmed by superior forces in conditions very much more favorable to them than to her. Probably Duke of York could have taken Scharnhorst in a true one-on-one battle, but that is not what happened off the North Cape of Norway in December, 1943. RICHELIEU type  This was intended to be a class of four ships, Richelieu, Jean Bart, Clemenceau and Gascoigne, but only Richelieu was completed to the original design. The first two were authorized in 1935 and the second pair in 1938. Jean Bart was about 77% complete when the Germans occupied France and she escaped to Morocco, at that time a French colony. She was completed after the war to a modified design and is covered in my essay The Post-Treaty Battleships. The last two were not completed at all, due to the outbreak of the war and the fall of France. Clemenceau was only about 10% complete when France capitulated and the hull was destroyed by Allied bombers on 27 August 1944. Gascoigne was to have been built to a revised design with one main battery turret fore and one aft. She was never laid down. The Richelieu class was to have been an answer to the Italian Littorio class, only the French actually tried to stay within the Treaty limits. In this they did a reasonably good job, as the Richelieu was widely regarded as equal or superior to the much larger (by approximately 5,700 tons) Littorio class. This was an important comparison at the time Richelieu was designed, as France and Italy were engaged in a Mediterranean naval arms race. Richelieu was designed to carry eight 15 inch, 15-6 inch DP, 8-37mm AA and 24-13.2mm light AA guns. During trials (conducted postwar) she made 32.5 knots. A hefty 37% of her displacement was allocated to protection, which was adequate against 15 inch shellfire. In that sense she was probably the best balanced of the fast battleships that were actually designed to conform to the Treaty, as she carried 15 inch guns and was adequately protected against 15 inch gunfire. You can make a pretty good case for Richelieu as the best of the treaty battleships. The Scharnhorsts and the KG Vs had the armor, but not the main battery. The North Carolinas had 16 inch guns, but not an equal level of protection. The South Dakotas had 16 inch guns and the armor to protect against them, but were very cramped ships compromised in other ways. The Nelson class were really the last of the second generation dreadnoughts and were seriously deficient in speed. The French 1935 pattern 15 inch gun fired a 1,938 pound shell at up to 35 degrees elevation to a maximum range of 50,000 yards. It could fire at a rate of 1-2 shells per minute. Richelieu's magazines would accommodate up to 832 of these big 380mm shells. Her broadside weight was 15,504 pounds. Richelieu's eight 15 inch guns were carried in two quadruple turrets, both forward in "A" and "B" positions. Her nine 6 inch DP secondary guns were in three triple turrets, all aft (two side by side in what would have been "X" position and one in "Y" position). This awkward disposition was duplicated in Jean Bart, but was to have been changed in Gascoigne to a one forward and one aft main battery turret arrangement. This would have solved the problem of the blind arc aft, but not the problem of having too many eggs (guns) in one basket (turret). A partial answer was that the French quadruple turret was internally divided in half longitudinally. This was supposed to reduce the chance of a single hit destroying all four guns. Even if true, it would not prevent a hit at the top of the partition from putting all the guns in the turret out of commission and any hit which jammed a turret would in effect put half of the ship's main battery out of action. The two main battery turrets were widely spaced to prevent a single hit from incapacitating both of them and to minimize blast interference. A wise precaution which, unfortunately, partially negated the supposed savings in weight of armor that was the reason for the design in the first place. The six inch DP secondary guns were not very satisfactory in the AA role and being as they were all disposed aft, they could not engage targets in a very large arc forward. In the Autumn of 1943 the light AA battery was substantially increased during a refit in the U.S.A. to 56-40mm and 48-20mm guns. At the same time radar was added and the catapults and aircraft removed. Bunkerage was increased by 500 tons. Complement was increased. These changes caused displacement to rise by about 3,000 tons. Richelieu was an unusual ship in appearance, but not ugly. She had a very long fore deck with two widely spaced main battery turrets, a tower superstructure and a combined funnel and after superstructure. The quarterdeck was cut away and some AA guns were placed there. The catapults and aircraft were originally placed amidships, between the fore and aft superstructures. The front half of the ship resembled the earlier Dunkerque class, but the back half was completely different, and more attractive. Richelieu's specifications:

Richelieu was laid down on 10 October 1935 and completed in July 1940. She was 95% complete when France was over-run and sailed to Dakar to escape being seized by the Germans. There, she was damaged when the British attacked. She survived and joined the Allied cause as a Free French ship in 1942, when she was sent to America for a complete refit. She served with the British Eastern Fleet in 1944-1945. She later served during the war against the Communists in French Indo-China (Vietnam). She was decommissioned in 1959. I have never heard any negative reports about her quadruple 15 inch turrets, so presumably they worked as designed. Regardless, I am very suspicious of quadruple turrets. Nor do I approve of only two main battery turrets, no matter how many guns they contain. Any design that concentrates all the main battery guns forward (and all secondary guns aft) seems seriously flawed. Nevertheless, I am forced to admit that Richelieu proved satisfactory in service and was superior to the rival Littorio class in the opinion of most experts. I would rate them about equal in ship to ship fighting power and give Richelieu the nod in most other areas. As noted earlier, Richelieu is a strong contender for the title "Best of the Treaty Battleships." KING GEORGE V class  The five ships of the British KG V class: King George V, Prince of Wales, Duke of York, Anson and Howe, were all laid down in 1937. They are often criticized as inferior to the contemporary German Bismarck class, but their critics fail to recognize that the Royal Navy ships were originally designed within the 35,000 ton treaty limit, while the German ships exceeded the limit by approximately 7,000 tons. The KG V's should properly be compared to the German Scharnhorst class, which were of approximately the same size, or the French Richelieu, or the American North Carolina class. These ships were also designed to the treaty limits. Such comparisons are interesting, because they reveal something about the military and political thought of the period. The British government desperately wanted to limit main battery guns to 14 inches. Consequently, they insisted their new class of battleships be designed to carry 14 inch guns. The United States was lukewarm to this idea, really preferred the 16 inch gun, but went along and initially designed the North Carolina class for 14 inch guns. The French wanted ships equal to their Italian rival's latest design, which required 15 inch guns and armor sufficient to protect against 15 inch shells. However, they also wanted to stay within the 35,000 ton treaty limit (which the Italians ignored). The Richelieu was an unusual and compromised design, but she had the balance of gun and armor desired and did it on approximately 35,000 tons. She was authorized before the 14 inch gun limit came into effect. Initially, the KG V design called for 12-14 inch guns in three quadruple turrets. Twelve guns was regarded as necessary to achieve the total broadside weight desired for the new ships, given the 14 inch bore restriction. Unfortunately, stability and protection considerations later required that the superfiring "B" turret be reduced to a twin mount. This gave the ships only 10 guns and required the design of two new types of turrets, rather than just one. Fortunately, the new twin mount could be based on the tried and true 15 inch twin mount, but the new quadruple mount was complex and took a very long time to sort out. Given the Royal Navy's experience with triple mounts on the Nelson class, it might have been better to design a 14 inch triple mount that could (presumably) be made to function correctly from the outset. The new ships would then have nine 14 inch guns in three turrets that worked, rather than 10 guns, eight of which were in unreliable quadruple mounts. At any rate, these ships were criticized, primarily because of their main battery, for the rest of their lives and some of the criticisms were justified. In service, the 14 inch quadruple mount had a very poor record. At times during the action against Bismarck, only POW's 'B' position twin turret was able to fire at the enemy. It is reported that KG V also suffered from turret breakdowns in her action against Bismarck. This has received much less attention that POW's problems, probably because the Royal Navy certainly did not want the word to get out that their new battleships had defective main battery turrets, and also because Rodney was there to take up the slack in the final fight against Bismarck. The other big fight involving one of the KG V class was DOY against Scharnhorst and I have read mixed reviews. At least one source claimed that (at last) the quadruple turrets worked as designed, but others (including Conway's) suggest that trouble with the quadruple mounts still persisted. I do not know the truth of the matter, but Scharnhorst was sunk at the end of 1943, three years of continuous war duty since the introduction of the 14 inch quadruple mount. One would think that if it had not been made to work by then, it never would be. All in all, the service record of the British 14 inch quadruple mount is not inspiring. The KG V class has also been (justifiably) criticized for being very wet forward. This was due to a design requirement for "A" turret to fire directly ahead at zero elevation. The KG V's tactical diameter was rather large at 930 yards. In addition, they were hampered by a very short range, due to their small oil capacity. This limited their usefulness in the Pacific war, as they carried only a little over half of the fuel carried by a similar size U.S. battleship. The dual purpose 5.25 inch secondary mounts proved to be too slow firing in the heavy AA role. They only elevated to 70 degrees (instead of 90 degrees) and the twin turret was overly crowded. On the other hand, these dual purpose guns were better value for the weight than the single purpose secondary battery of the third generation German and Italian battleships. The KG Vs also had their good points, a fact sometimes overlooked by their critics. Their armor was generally heavy and extensive, except on the secondary turrets and CT. The main belt was very deep, extending 13 feet below the waterline at mean draught. The main deck armor was six inches over the magazines and five inches otherwise. The underwater protection scheme was designed to withstand a 1000 pound TNT charge at its most favorable point. All of this made the KG Vs generally better protected than the other treaty battleships, with the possible exception of Richelieu. Their internal layout was certainly better than Bismarck's and their radar fire control was superior to anything possessed by the Axis powers. Scharnhorst, for example, was completely surprised when DOY opened fire on her using radar control in thick fog off the North Cape of Norway in the middle of winter. The new 14 inch gun was a potent weapon. It fired a 1,590 projectile at a MV of 2,483 fps to a range of 38,550 yards at 40 degrees elevation. It was claimed that the 14 inch AP shell penetrated any given thickness of armor at a greater range than the earlier British 15 inch shell. Simple arithmetic shows that a full broadside from KG V weighed 15,900 pounds and a full broadside from Richelieu weighed 15,504lb. Bismarck's broadside weight was somewhat less than Richelieu's. Seen in this light it is apparent that the KG V's were not particularly under gunned compared to other contemporary European battleships. Their specifications were:

Because the war broke out and the Treaty lapsed while these ships were still under construction, they were allowed to grow above the old Treaty limit in displacement. They were to grow still more as the war went on and new equipment was added, particularly radar and more light AA guns (up to 65-20mm Oerlikon, eight octuple two pounder pompoms plus six quadruple pompoms and up to 14-40mm Bofors in quadruple and single mounts). By 1945 Anson's extreme deep load displacement was up to 45,360t. Stability suffered accordingly. King George V was completed in December of 1940, Prince of Wales and Duke of York in 1941, and Anson and Howe in 1942. POW was sunk at the end of 1941; the four survivors were broken up in 1957. They all had very active war careers. Their most spectacular moments were POW's fight against Bismarck in company with Hood, May 1941, in which POW was hit repeatedly, but none of her vital systems were put out of action by enemy shellfire; KGV's participation in the defeat and sinking of Bismarck a few days later (as Home Fleet Flagship); and DOY's defeat of Scharnhorst in late December 1943. The only wartime loss was POW, which (along with the battlecruiser Repulse) was sunk off the coast of Malaya by a series of air strikes made by large numbers of Japanese land based naval bombers on 10 December 1941. She became the first (but certainly not the last) battleship sunk underway at sea by aircraft. This event, more than Pearl Harbor, signaled the end of the battleship's years as the dominant class of warship. NORTH CAROLINA class  The first pair of American treaty battleships were the North Carolina and Washington, laid down in 1937 and 1938 respectively. However, their story started earlier, in 1935, as they were the result of a long series of design studies and compromises. The requirement for fast battleships was becoming evident, forcing the USN away from the slow (23 knot), heavily armed and armored type it had traditionally preferred. The CNO (Chief of Naval Operations) expressed the view that was eventually adopted: enough speed to run down the fastest capital ships in the Pacific (the Kongo class, then rated at 26 knots). The four Kongo class battlecruisers were regarded as a particular "thorn in the side" by USN strategists in the years preceding WW II. This meant the new U.S. battleships should make a minimum of 27 knots. All subsequent U.S. battleships, except the special purpose Iowa class, would be designed to this standard. When polled, the senior officers with the Fleet favored the fast battleship by a nine to seven margin. The senior officers in the War Plans Division favored the fast ship by a greater five to one margin. In March of 1934, Japan had announced that she would not renew the naval treaties when they expired. As we have seen, the London Treaty of 1936, which was being negotiated as the North Carolinas were being designed, called for 14 inch guns and 35,000 tons, but had escalator clauses to allow 16 inch guns and 45,000 tons if a non-signatory did not abide by the spirit of the treaty. Japan's noncompliance triggered these escalator clauses in time to provide 16 inch guns for the North Carolinas, but not equivalent armor protection. The design was by then too far advanced to allow much change in the protection scheme. In fact, the 16 inch guns were only possible because the design called for 12-14 inch guns in three quadruple turrets and these had been designed with the same turret ring size as the triple 16 inch turrets BuOrd had wanted all along. BuOrd was not happy about reverting to the 14inch gun for the new battleships, or with the risks inherent in developing a quadruple turret. Japanese non-compliance allowed BuOrd to have its way and make America's treaty battleships the most powerful of the type. The complexity and evolution of the design selection process is interesting. The following information on this topic is summarized from Norman Friedman's definitive book on the subject U.S. Battleships - An Illustrated Design History. In all, 15 preliminary sketch designs were considered and variations of the most promising were analyzed. Each was identified by a letter of the alphabet. The preliminary design finally chosen for further development ("K") was a 30.5 knot proposal with nine 14 inch guns in three triple turrets, all forward of the superstructure (as in Nelson) and a 15 inch armor belt (immune zone 19,000-30,000 yards) on a 710 foot hull. Several months passed before it was discovered that this layout did not result in the weight savings envisioned. Sketch designs in the next step of the selection process, as the original "K" proposal was refined, eventually numbered 35! These were assigned Roman numerals. Variations in armament, armor, hull length, torpedo protection, speed, internal layout, in fact almost every specification, were explored. The first of this series were numbers I through V. In January 1936, Scheme IV was selected for further development. This design showed a 725 foot hull on which was mounted nine 14 inch guns and a 12.125 inch belt (immune zone 21,400-30,000 yards). The speed was to be 30 knots. However, the General Board wanted major changes, including 20 five inch secondary guns, rather than the 12 carried by design IV. This resulted in three further sketch designs: IV-A, IV-B and IV-C. None met the Board's requirements, particularly in terms of protection. By May 1936 the General Board relented on very high speed; 27 knots was perhaps adequate, if more armor could be worked in. Designs numbered up to XV-E had been explored by the middle of June 1936. On June 25, the Board issued new tentative characteristics. Now they wanted a 28.5 knot ship with 11-14 inch guns and 16 five inch secondary guns. The immune zone was to extend from 19,000 to 30,000 yards. This was a specification well balanced between speed, battery and protection. Preliminary Design responded with design XVI on 20 August 1936. This had a 714 foot hull, 12-14 inch guns in three conventionally laid out quadruple turrets, an 11.2 inch belt sloped at 10 degrees and a 27 knot top speed. As the wrangling continued over the new battleship's design, XVI-A, XVI-B, XVI-C and XVI-D appeared. XVI-C, in particular, was widely debated. It was 725 feet long, carried nine 14 inch guns, a 13.6 inch belt and made 30 knots. For a time this design was supported by the General Board. In October of 1936 the characteristics of the new battleship were again revised by the General Board. Underwater protection was to be improved (tests had shown this to be necessary), the main armor belt thickened and more sharply angled, and more secondary guns worked in. Speed was allowed to decrease to 27 knots. This time the revised characteristics were signed by the Acting Secretary of the Navy, with the provision that the design allow 16 inch guns (in triple turrets) to be substituted for the planned 14 inch guns (in quadruple turrets), if necessary. A detailed design was then prepared that became the North Carolina class. In March 1937 the gun caliber clause in the London Treaty was invoked and in July 1937 BuOrd finally got the 16 inch guns they had campaigned for all along. Nine 16 inch guns would be more effective than 12-14 inch. In addition, a triple turret was far less risky that the proposed quadruple turret. The North Carolina design, as planned, had been well balanced, carrying 14 inch guns and adequately protected against 1,500 pound 14 inch shells. With the adoption of the 16 inch gun (then firing a 2,250 pound shell), the immune zone against 16 inch AP shells shrank to 21,000-27,700 yards over magazines and only 23,200-26,000 yards over machinery. Note that the ship's armor had not changed, just the standard of comparison. Interestingly, against the U.S. 16 inch / 2,250 pound AP shell, Japan's 16 inch gun battleships, the Nagato class, had no immunity at all! In fact, by the start of the Pacific war, North Carolina and Washington carried the new super heavy 2,700 pound 16 inch shell, against which they (and most other battleships in the world) had virtually no immune zone. This new shell made the American 16 inch gun nearly equal to the Japanese 18.1 inch gun (3,220 pound AP shell) carried by the giant Yamato class. The specifications of the North Carolina class (as built) were as follows:

In appearance, North Carolina and Washington were handsome, well proportioned and well balanced ships with a flush deck and a conventional layout. Twin funnels, a graceful prow, a tall fire control tower and a cruiser stern were recognizable features of their design. I have always regarded them as the most handsome of all U.S. battleships (see my article "Great Capital Ships, 1920 to 1990"). North Carolina was commissioned on 9 April 1941 and Washington on 15 May 1941. Severe (unforeseen) propeller vibration problems on trials at speeds from 25-27 knots caused various propeller combinations (3, 4 and 5 bladed types of various diameters) to be experimented with. The North Carolina received the nickname "Showboat" due to her many trips in and out of New York harbor during these propeller trials. During December 1941, Washington made 28 knots at 42,100 tons and 27.1 knots at 45,000 tons at full power. Like all wartime battleships, the North Carolinas received increased electronics and AA battery as the war went on. By August 1945 the Washington carried 15 quadruple 40mm Bofors mounts, one quadruple 20mm mount, eight twin 20mm mounts and 63 single 20mm mounts. The best point of the class was probably their offensive firepower. Their main battery, with a broadside weight of 24,300 pounds, was second only to the Yamato class that were almost twice their displacement. They (and the similar South Dakotas) also carried the best secondary battery, the best AA battery and the best fire control of all treaty battleships. They were extremely maneuverable, with a tactical diameter of 575 yards at 14.5 knots. They had great range and endurance, again superior to the battleships of all other nations. They were seaworthy. Their underwater protection was superior to that of the other American 3rd generation battleships. They were later criticized for being "unbalanced" (armament vs. armor), but it must be remembered that, in fact, they were adequately protected. If they had been completed with 12-14 inch guns, as originally planned, they would have been "balanced" and no one would have complained. Substituting the triple 16 inch gun turret for the quadruple 14 inch gun turret on a one-for-one basis did not make the ships any larger or heavier; it just gave them a much more effective offensive punch. It was only the marked superiority of the American 16 inch gun and super heavy 2,700 pound shell (compared to the gun/shell combination carried by all other nations' Treaty battleships) that made them seem "unbalanced." A useful analogy might be this: which would you rather put your money on, a heavyweight boxer with a good chin and a good punch, or one with a good chin and a great punch? In theoretical comparisons made by BuShips in December 1941, the North Carolinas fared well against either King George V or Bismarck. Both ships served throughout the Second World War, participating in a great many campaigns in both the Atlantic and Pacific. They proved to be very satisfactory in service and were generally regarded as superior in operation to the very cramped South Dakota class that followed. The most significant moment of North Carolina's wartime service occurred when she was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-15, on 15 September 1942. The torpedo hit on the left side just behind number 1 barbette (and abeam the forward magazine), blowing an 18x32 foot hole in the hull. This let in about 970 tons of seawater and buckled the second and third decks. Within minutes the ship was able to make 24 knots. After the incident BuShips stated that the underwater protection system had performed much as designed and no changes were indicated. The North Carolina class underwater protection was superior to that of the subsequent South Dakota and Iowa classes (which verged on being defective, due to unwise changes in the whole theory of underwater protection), although this was probably not realized at the time. North Carolina, the famous "Showboat," was the only U.S. treaty battleship retained in active service post-war. In 1961 she was stricken from the Navy list, but preserved as a war memorial at Wilmington, North Carolina, where you can see her today.Washington became the most successful American battleship of WW II. Her most glorious moment in the war came during the night of 13-14 November 1942, when she sank the Japanese battlecruiser Kirishima in a wild night action called the Second Battle of Guadalcanal. Kirishima and her accompanying cruisers and destroyers had just disabled the new U.S. battleship South Dakota when Washington slipped to within 8,400 yards of Kirishima and overwhelmed her with 16 inch and five inch shellfire. Washington was not hit in this action, which was primarily a tribute to American radar, fire control and the offensive firepower of the North Carolina class. It is interesting that Kirishima was one of the Kongo class battlecruisers that, back in 1935, had so markedly influenced the concept that eventually became the North Carolina class. Washington was sold for scrap in 1961. Washington served with the British Home Fleet in 1942, but despite the hopes and prayers of her crew, the German super battleship Tirpitz never came out to fight. I have always thought that if she had, Washington would have surprised a lot of people by taking her without too much problem. SOUTH DAKOTA class  These four ships were the last of the treaty battleships. They were laid down about the time the war in Europe started and all were completed after the war in the Pacific had already begun. They were designed in accordance with the limitations of the London Naval Treaty, however, which is why they are covered here. The original plan was to build two more North Carolina class battleships in FY 1938. Due to pressure from the CNO a new type, which became the South Dakotas, was designed, scheduled for FY 1939. Preliminary design work began in March of 1937 and the characteristics of the new ships were approved in January of 1938. Congress appropriated the money to build them in April 1938 and, as war loomed on the horizon, authorized a second pair in June 1938. Their names were to be South Dakota, Indiana, Massachusetts and Alabama. In retrospect, it probably would have been wiser and more efficient to have built two more North Carolinas, which would not have required additional design work. Subsequent design and production effort could then have been focused on the six high speed Iowas, getting them into service earlier in the war. (Design work on these had already started by the time the second pair of South Dakotas was authorized.) The primary design goal for the South Dakota class was to incorporate protection against 16 inch shellfire, while staying within the 35,000 ton limit and maintaining the 27 knot speed of the previous class. The immune zone (against the 2,240 pound 16 inch shell) was to be 17,700-30,900 yards. This shrank to 20,500-26,400 yards after the introduction of the 2,700 pound AP shell. Providing adequate protection against 16 inch shellfire in a 35,000 ton battleship was a real achievement. Basically, it was accomplished in the following manner: 1. The hull was shortened and the vitals made even more compact than they were in the North Carolinas. To achieve this turbines and boilers were placed side by side, all main generators were steam powered (instead of diesel), the forward main generator room was dispensed with and the magazines were reduced in length by a total of eight feet, thus reducing the area requiring armor protection. 2. The armor belt, although not much thicker, was internal and more steeply sloped than the North Carolinas. The fundamental design goal was achieved, but the price was high: inadequate torpedo protection (in reality a greater threat to WW II battleships than gunfire), reduced seakeeping ability and extremely cramped and uncomfortable ships. All staterooms were reduced in size, as were the crews' berthing and messing spaces, which were no longer separate. The ships were wet forward, they had a very deep draft (which limited the harbors and dry docks they could use), they required more power to make the same speed (135,000 shp rather than 115,000 shp) and there was considerable blast interference between their closely placed guns. All of these drawbacks, except the flawed torpedo protection, stemmed from their short hulls. As the war progressed and light AA guns, electronic equipment and personnel were added, the crowding problem became acute. The problem with the torpedo protection system was a result of the armor scheme, which required a very rigid layer of armor far below the waterline to protect against underwater 16 inch shell hits. This negated the concept used in previous battleships, which was based on the deformation of relatively light and elastic bulkheads to contain the blast from an underwater explosion. Caisson tests, which revealed the flaws in the design of the new underwater protection scheme, were not performed until all of the South Dakota class were actually under construction. Likewise, the Iowa class design was virtually finished and its underwater scheme was similar to the South Dakota class. Nothing could be done for either class, except to fill the outboard void spaces with fuel oil, in the hope that it would absorb some of the energy from an underwater explosion. Significantly, the subsequent Montana class design reverted to an underwater protection scheme similar to the North Carolina's. The South Dakota class main and secondary battery was the same as the previous North Carolina class and the subsequent Iowa class, and the AA battery was similar. The broadside weight remained 24,300 pounds. All guns on the South Dakotas were more crowded than on the previous and later classes, however. South Dakota herself was fitted as a Force Flagship, with an additional level added to her conning tower, and she sacrificed two twin five inch mounts as weight compensation. Her secondary battery was therefore 16 five inch (8x2), rather than the 20 five inch guns (10x2) carried by the other three ships. The specifications for the class were as follows.

Visually the "short hulled" class (as they were called) differed from the North Carolinas and Iowas by having only one funnel. Their general layout was conventional, but their stubby hull and single funnel made them recognizable. They handled well and had good maneuverability, with a tactical diameter of 700 yards at 16 knots. Like the North Carolinas, the short hulled battleships were fitted with various combinations of 3, 4 and 5 bladed propellers, but they never suffered from vibration problems of the same magnitude. In 1942, Indiana made 27.8 knots at 41,700 tons. Alabama recorded 27.08 knots at 42,740 tons and 26.7 knots at 44,840 tons while being standardized in 1945. As with all U.S. battleships, the AA armament increased dramatically during the war. By the late stages of the war they carried 14 to 18 quadruple Bofors 40mm mounts and 40 to 84 Oerlikon 20mm guns in single, twin and quadruple mounts. The 1.1 inch and .5 inch AA guns had been deleted by that time. All four ships served in many campaigns during the war, mostly with the fast carrier task forces. Only once was one of them in a surface engagement, the night battle called the Second Battle of Guadalcanal, 14-15 November 1942. In this battle, South Dakota came under fire from the Japanese battlecruiser Kirishima and her attending cruisers and destroyers. She was hit by one 14 inch shell, 18 eight inch shells, a half dozen six inch shells and one five inch shell. Her fire control tower was badly shot up. Her surface search, air search and fire control radars were knocked out (with the exception of one set on the after control position). Most of the internal communications and fire control circuits were disrupted. The concussion of the aft turret firing astern caused more electrical problems, set the float planes on the fantail on fire and subsequently blew them overboard. Although her main armor was not penetrated and she was in no danger of sinking (as usual, Japanese AP shells performed miserably) and her main battery remained functional in local control, the ship was effectively deaf, dumb and blind. She was put out of action during the height of the battle and would have been at the mercy of her enemies if Washington had not been there to blow away Kirishima and save the day (night). During the Allied invasion of North Africa, the incomplete Vichy French battleship Jean Bart, with only one of her quadruple 15 inch turrets operational, opened fire on the invasion fleet. Massachusetts returned fire and quickly knocked her out of the fight and the war. Jean Bart was severely damaged and was not repaired and completed until 1949, becoming the only French post-treaty battleship. After the war, all of the short hulled class were almost immediately decommissioned and placed in reserve. South Dakota was sold for scrap in 1962 and Indiana suffered a similar fate in 1963. Massachusetts and Alabama were preserved as war memorials in their respective states and are partially open to the public. The final verdict on the South Dakota class is mixed. In a theoretical one-on-one gun battle (the kind of occurrence that in reality never happened), they were probably the best of the treaty battleships. Yet in actual service they were regarded as inferior to the previous North Carolina class. CONCLUSION In the course of this essay I have occasionally made reference to the hypothetical title "Best of the Treaty Battleships." Making such a selection must be both hypothetical and personal. All of the treaty battleships were heavily compromised to a greater or lessor extent by the need to at least nominally conform to the limitations of the various international naval arms limitation treaties. All of them could have been improved had these restrictions been lifted, as the post-treaty Iowa class and Vanguard were. The term "best" is itself open to various interpretations. To me it implies a balance of qualities, the most generally useful battleship, not just the battleship theoretically most likely to win a one-on-one gun battle. I look at it this way: If I were the Chief of Naval Operations of a major navy, which type would I select to operate in WW II? Rodney (too slow) and Scharnhorst (too little firepower) get eliminated immediately. However, in reality both served well in WW II. That leaves Littorio, Richelieu, King George V, North Carolina and South Dakota. These were all good ships. Any of these could be the top choice, depending on the viewpoint of the person doing the choosing. Since in this case it is me, I am going to drop Littorio (displacement too far over the treaty limit, guns too experimental and maybe too vulnerable to underwater damage) and King George V (range too limited and quadruple turrets too complex) from further consideration. This leaves three, all winners. The second runner-up is . . . South Dakota! The top gunfighter has great range, good protection and adequate speed. However, she is compromised operationally in seakeeping qualities and habitability. The first runner-up is . . . Richelieu! Well balanced, fast, only her unusual layout relegates her to second place. The "Best of the Treaty Battleships" is . . . North Carolina! Adequate or better in every category, particularly firepower (main, secondary and AA all second to none), fire control, sensors, maneuverability and range. Her superior seakeeping qualities and habitability lift her above South Dakota and her superior main battery and sensible layout edge her ahead of Richelieu. |